By Dr John Bacher and Danny Beaton, Mohawk of the Turtle Clan.

In Memory of Alicja Rozanska.

In December 1990, I journeyed with the Mohawk environmentalist Danny Beaton to the Innu community of Sheshatshiu. We undertook our journey for an important purpose. We travelled to stop the use of the vast landscape of the Labrador-Quebec peninsula, at that time known as Ungava, as a playground for military aircraft of various states of the NATO alliance. Jets were flying low and terrifying caribou and Innu hunters. They polluted lakes with jettisoned engine fuel. The military planes were also dropping bombs for testing. There was an odious wasteland where bomb testing was carried out that was officially denied. It was discovered when Innu, under the leadership of Elizabeth Penashue, went into a forbidden zone. Here they found a land marred by crater holes from bomb dropping, exposing the lies of those who apologized for the use of the Innu’s caribou hunting grounds for war games.

We were told of the horrible shock that the Innu experienced from the decline of caribou hunting among their people. Boredom from living in the communities of Sheshatshiu and Davis Inlet (an island isolated from caribou habitat, which was eventually relocated to the mainland after outrage over deaths from gasoline sniffing) had devastating consequences. Innu youth had some of the highest levels of suicide in the world. We were constantly told that hunting and fishing trips during the summer always brought sanity to the most disturbed.

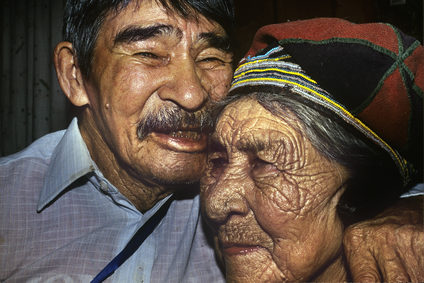

In our meetings in Sheshatshiu, what hammered home oppression was our visit with a couple, the Pasteens. They were determined to maintain traditional ways. They dried fish on wood in the open air in the ancient manner. Micahel Pasteen explained to us how his hunting cabin and its equipment had been flooded out by the rising waters of Lake Smallwood in the 1950s. It was constructed without the Innu’s consent or any compensation for a hydroelectric dam. To refute justifications for low level flying, the wise Innu elder made a simple comparison: the jets avoided cattle pastures, but ravaged forests that nurtured the caribou that the Innu depended on.

Recently, I came upon a disturbing finding that explains why supersonic flights have gone the way of the extinct Dodo bird. Now aircraft flying low can be damaged from explosions conducted for new quarries and mining exploration. Explosives from mining exploration have stopped the war games that were carried out despite arrests of Innu activists from walking on the airport that was on their unceded land. Now, the wilds of Ungava are littered with a thousand mining exploration camps, which keep the jets away, but pose worse threats to the caribou. More devastating are the new roads and the clear cutting of mature forests, rich in lichen that caribou need to eat in the winter.

When we arrived in Sheshatshui there were 1.5 million caribou living in Ungava, populated by 60,000 Indigenous Innu, Cree and Innuit people. While the number of the Indigenous people is about the same, caribou numbers have collapsed to around 250,000. The largest is the Leaf River herd. It is around 200,000. This is less than half of its size of 600,000 in 1990. It is the only caribou herd in the Quebec-Labrador peninsula where any hunting is permitted. Recreational hunting here by non-natives was only banned in 2018 after alarm by the Cree and Innuit that the herd’s size had shrunk in half. The Innu of Labrador are currently not permitted to hunt here, but negotiations are underway.

The herd is threatened by an explosion in mining development and new roads. In 1990, the George River caribou herd was the world’s largest gathering of migrating mammals. The herd was 750,000 strong. It migrated on a North-South basis across the Labrador-Quebec peninsula from the tundra where the George River flows into the Arctic Ocean, to its forested wintering grounds. It is now made up of just 8,500 caribou. This is an increase from a low of 5,000 just three years ago, helped by a strictly enforced hunting ban. But no protected parklands have been established within its range.

One factor in the George River’s collapse was the pushing of service roads through the herd’s critical calving ground. It opened in 1994 and serviced the Voisey Bay Nickel mine. The Trans Labrador Highway sliced across its habitat. Roads help expose forests for the first time to clear cut logging, which strips woodlands of the mature trees rich in lichens that the caribou need to survive on in winter months.

The vastness of the Quebec-Labrador Peninsula gives some complexity to its caribou herds. While they show strong site fidelity, there is some intermingling. In 1990, most caribou were in two great migratory herds. Herds of such great size have a beneficial impact on insulating permafrost from melting. This is important to stop catastrophic greenhouse gas emissions of methane. Herds of hundreds of thousands of migrating caribou pack down the snow reducing the danger of permafrost melt. The Leaf and George River herds are both termed Migratory Woodland Caribou of the forest tundra ecotype. The collapsed great caribou herds had an impact upon the land, as shown by how caribou trails are in aerial photos. With the collapse of the George River herd, the brush has grown up from the end of the trampling actions of herds. The impact has been demonstrated by analysis of test plots of vanished trails by biologists.

There are several smaller herds that roam the vastness of Ungava. One is of a distinctive subspecies called Mountain Caribou. It ranges in the Northern Torngat Mountains, the Northeastern tip of Ungava. There are three herds of Sedentary (non-migrating) Woodland Caribou. These are the Red Wine, Mealy Mountain and Lake St. Joseph. The most devastated of these herds is the Red Wine. The Red Wine Herd has shrunken to around one hundred caribou. Its range includes the most urbanized area of Ungava around Happy Valley Goose Bay. This community depends on the military base and the forestry sector. The threatened Red Wine’s herd range is where most of the clear cutting in Ungava takes place.

In 1990, the collapse of the George River herd was unimaginable. We were told by the elders, however, that they were appalled by the waste of recreational hunters. We were shown a film about the Quebec North Shore Labrador railway. It runs through the heart of the shrunken St. Joseph Lake Caribou herd. The film documented how rail cars were filled with the antlers collected by recreational hunters to take to distant homes for trophies. The herd, which numbered 1,282 in 1970 when first counted, now has plunged to 210 caribou. When we visited elders such as Francis Penashue, they pleaded to ban recreational hunting. However, the elders were dismissed by claims, now discredited, that caribou were overgrazing their range. His advocacy for caribou, still carried out by his widow, Elizabeth, is now recognized as “one of the power and possibility of personal transformative changes.”

“Caribou”, explains Laval Professor Steve Cote, “are not lemmings.” His words are reinforced by Grad Griffith, an American biologist who is an advisor to the Gwitchin. What caribou need are great ranges to roam to adjust to periodic changes in precipitation and vegetation. Defenders of mining and related road construction in the Quebec-Labrador Peninsula excuse climate change as the driving force behind the demise of caribou as part of the diet of Indigenous peoples. Climate change’s worst impacts on caribou herds are largely confined to those of the Barren Ground herds of North West Territories. These migrate from islands to the mainland across ice. For some subspecies, notably the Peary, migrating animals now often crash through thinner ice triggered by anthropogenic disruption of temperatures. The Peary’s collapse has made it an endangered subspecies.

The herds of Ungava do not cross sea ice. They resemble in their range conditions those of the Porcupine caribou, another forest-tundra ecotype. The difference is that mining, dams, clear cuts and roads (with the exception of a small tract of the Dempster Highway located on its Eastern edge), have been kept out of the range of the Porcupine herd. Its success is from the determination of the Gwitchin Nation on both sides of the Alaska/Yukon boundary and their environmentalist supporters. They have defeated even powerful petroleum interests, most recently, the supporters defeated former U.S. President Donald Trump.

The Ungava herd that shows the most promise for recovery is the Mountain Caribou herd of the Torngats. The Inuit have protected the Torngat herd by the same strategies employed by the Gwitchin. This is a strategy of designating parks and other protected areas entrenched through land claim agreements to protect caribou. While in the Eastern half of its range, the Mountain Caribou herd is protected by the Torngat National Park, the herd in Quebec is safeguarded by the Kuururjuaq Provincial Park. There are two other areas that are calving grounds protected under Quebec legislation as wildlife habitat. These two parks, about 15,000 square kilometers, are the most substantial areas of caribou habitat in Quebec protected from the province’s frenzied mining craze.

Through their land claims, the Innuit of Nunavik (Labrador) secured both the creation of Torngat National Park and a requirement that all of its paid staff be members of their nation. The result is that the Torngat Herd of Mountain Caribou is the only Ungava herd that has escaped collapse and is slowly increasing. The success of the herd is in vivid contrast with the rest of the region. Torngat National Park was created as a park reserve in 2005, banning all mineral exploration and development. Gradually, after it was formally established and staffed by the Innuit, serious scientific research was done on the Torngat caribou herd.

In 2014, a herd census found 930 caribou. This has now increased to 1,426. Biologists have found that the biggest barrier to growth has been the collapse of the once great George River. Its demise made the Torngat Mountain caribou more vulnerable to wolf predation. The ecological focus of Torngat National Park and how it is closely tied to Innuit strategies for economic development and cultural survival is celebrated through its interpretive center. It is combined with a scientific research base camp. The center is surrounded by an electrified polar bear exclusion fence. Innuit obtain employment as Bear Guards taking visitors beyond this protected perimeter.

The largest area of protected caribou habitat in Ungava is the Mealy Mountain National Park Reserve, established in 2015. The reserve’s 10,700 square kilometers makes it the largest protected area in continental Eastern North America. One old mining claim was purchased when the park reserve was created. Logging and mineral exploration is now prohibited. The park reserve contains spectacular rugged mountain scenery and ocean inlets. Six years later, since negotiations with the Innu have not been completed, there is no administration center or park trails. This will only come after a national park is established through federal legislation.

While the government of Newfoundland has promised a 3,000 square kilometer Eagle River Waterways park, the area to be protected is still not defined and remains vulnerable to mining exploration. One of the key reasons for the park reserve’s creation, first proposed by the Federal government in 1976, was to protect the range of the Mealy Mountain caribou herd. Following a population collapse for about two decades, the herd now hovers around 250 caribou. It is the only stationary caribou herd in Ungava to have a substantial part of its range protected from industrial development.

Of all the people Danny and I met in 1990, Elizabeth Penashue stood out by her determination to protect the land and her people from boredom and substance abuse. She exposed the secret NATO bombing base. Elizabeth Penashue led opposition to the Lower Churchill Dam. Its reservoir destroyed 100 square kilometers of the range of the George, Red Wine and St. Joseph herds. Her great victory so far has been to achieve the Mealy Mountain National Park Reserve. Elizabeth Penashue was concerned that the Innu, especially youth, bottled up in nearby Sheshatshiu, would lose their connection to the Mealy Mountains. She led ten-day snowshoe trips into the mountains of groups of around twenty people.

The pattern of protection of Ungava approximates the challenges for defending the landscape from ecological abuse in much of the world. The landscapes deemed worthy of protection are frequently glaciers and mountain peaks, which have been termed a rock and ice aesthetic. While new schemes of industrial exploitation constantly emerge in a mining rush, plans to protect new areas are bogged down in a mire.

One of the most dramatic impacts since our visit was the opening of the Raglan Nickel Mine in 1997. One of the worst impacts of the mine was its need to have a 100 kilometer road constructed through the range of the Leaf River Caribou herd to an Arctic Ocean port on Deception Bay. Just East of Raglan, the Quebec government is being lobbied for three new Iron mines, all of which would have roads pushed through the Leaf River Herd’s range to Deception Bay. Another frightful project, which would be a blow to the recovering George River, is the proposed mining for the Ashram Rare Earth Deposit, needing a 185 kilometer road to the waters of Ungava Bay.

In all the vast range of the Leaf River Caribou herd there is only one protected area. This is Quebec’s Pingualuit Provincial Park. Although established largely to protect the pristine waters of a meteorite-created lake, the park also protects 3.3 per cent of the calving ground of the Leaf River caribou herd. That such a miniscule area is protected shows the urgent need to make more land off limits to mining and mining exploration within its Leaf River herd’s range.

The wise words of native elders are expressed in a report “A Long Time Ago in the Future; Caribou and the People of Ungava.” Here the elders stress that “having respect will encourage the caribou to come back again”, but that “with the way that the caribou has been treated in the last decades”, there is a danger “that the caribou will disappear and never come back again.” One way of showing respect is to protect enough of Ungava’s landscape, so that they can continue to roam.

Our elders teach us to talk to the caribou and the caribou will talk back to us; but if we don't talk to the caribou, how can the caribou understand us Human Beings? And if we don't understand the caribou, we may hurt them and if we hurt the caribou, we may hurt ourselves. Everything on this sacred Mother Earth has a Spirit. Everything on this sacred Mother Earth is alive. Somehow many humans have not been conscious of the many wonderful life species living everywhere around us. The caribou is not to be seen in many forests in Southern Ontario, but in the Northern communities, they are alive and respected by Indigenous people everywhere.

In the old days they gave us Indigenous people food, clothes, shelter, medicine, even drums and crafts. Indigenous people learned to respect our animals just as they respected Mother Earth. They learned that all life was connected and one. Today that has changed in many ways, but there are still Indigenous people respecting our old ways of protecting all of Creation. Our sacred ceremonies honour everything that moves on Mother Earth: first the plant life, then Mother Earth’s Blood/the Water, then the four-legged, the winged ones, the fish life and insects creeping, crawling. Our caribou, moose, bear, deer, rabbits, turtles and everything that is moving is being killed or injured by extension roads and highways. Alaskan Governments started looking at ways to protect our animals, but there are still casualties.

Mining, logging, overhunting and urban sprawl have caused a collapse of caribou herds in Canada, including the practice of war games by test pilots in the past. All animal species have been suffering in British Columbia from pollution and urban sprawl. We Human Beings are supposed to be the voice for all life on this sacred Mother Earth. How can we allow such madness to continue to destroy our children's future and their children’s?

Photo credit: Pasteens Innu Elders by Danny Beaton, Winter 1990.